Matthew Rodgers spins a yarn on the work of M. Night Shyamalan

Are you sitting comfortably? Good. Then we shall begin. Close-up Film wants to tell you a bedtime story. A story involving ghosts, comic book characters, aliens, woodland dwelling beasties and a young man whose imagination and ambition has marked him as one of the only autuers operating in Hollywood today, and one of the single greatest storytellers since Spielberg.

Our tale starts in the year 1999, at the end of a decade screaming out for originality, set in a movie landscape saturated by revealing trailers and predictability. M. Night Shyamalan was about to emerge from nowhere to release a cultural phenomenon upon an unsuspecting world. The director was completely off the radar after little seen efforts such as Praying with Anger (1992), in which an alienated young American of Indian origin returns to his homeland to discover himself, and the similarly thematic Wide Awake (1998), which focused on a 10 year old boy on a search for God after his grandfather dies, failed to earmark him as a talent to watch.

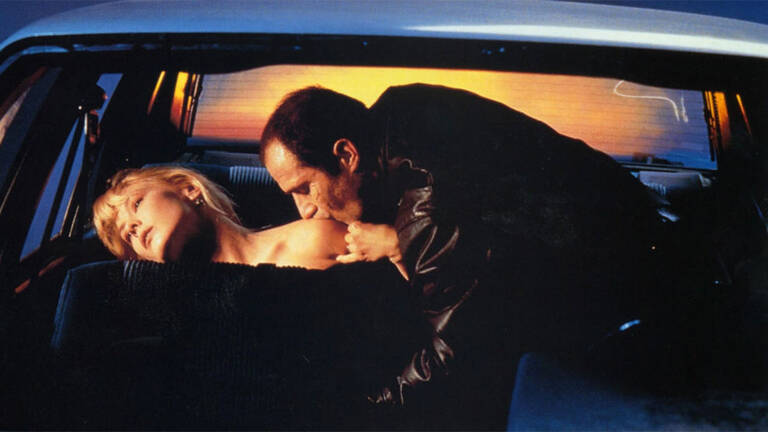

The Sixth Sense (1999) was released in the same weekend as a certain over-hyped (yet successfully scary) independent movie called The Blair Witch Project (1999). There is little doubt that media interest in Blair Witch had meant that Shyamalan’s film was reaching an audience who had heard very little about it. Good marketing on the studio’s part, a lucky coincidence, or the first sign of a director who has been accused of having little more than a few tricks up his sleeve?

Whatever the cynics say about Shyamalan being a “one trick wonder” his passion for film is unrivalled. He began making films at the age of 10 and by the age of 16 he had amazingly completed his 45th short film (some of his early efforts are available as extras and easter eggs on dvd releases of his movies). A son of two doctors and a family history in the medical practice meant that his early path was signposted towards Dr. M. Night, until at the age of 17 he enrolled at the New York University Tisch School of Arts to study filmmaking.

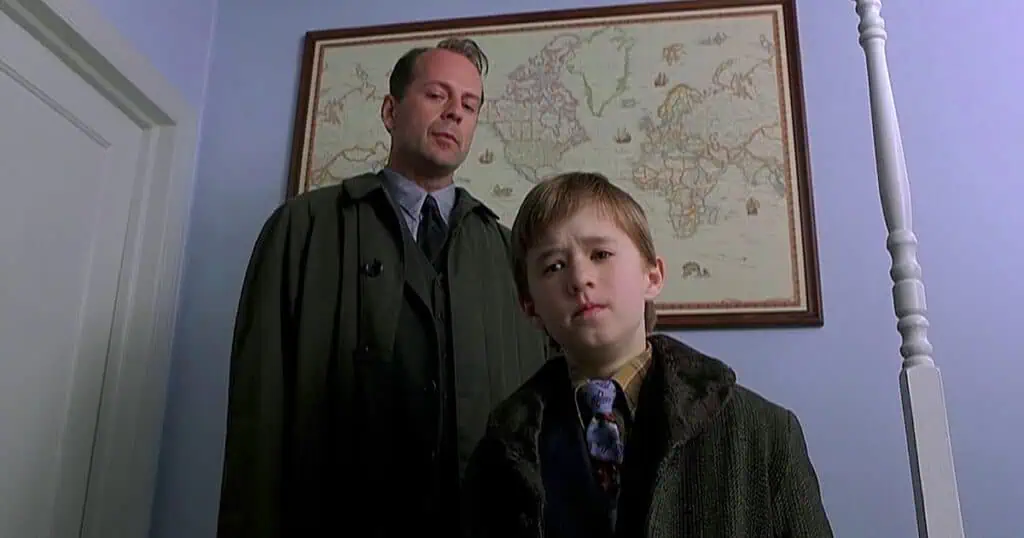

The Sixth Sense (1999) was a psychological thriller that was character driven with some genuine scares (who wanted to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night after “that scene”?). It was a class above the rest of the genre’s offerings, and would subsequently be “ripped off” with the likes of Hide and Seek and Stir of Echoes. An understated turn from Bruce Willis, who had been known as an action star up until that point, and an Academy Award nomination for its 10-year-old lead, Hayley Joel Osment would be added to a poster already boasting nominations for Best Picture and Best Director.

All of the accolades, awards, and huge global box office were down to one thing: word of mouth had meant that “that ending” had become the most talked about secret in Hollywood, in school yards, and in the pub. Avoiding having the twist spoilt for you, or asking “have you seen The Sixth Sense?” became a common topic. The sort of marketing that money couldn’t buy. It also meant that Shyamalan would be given a lucrative deal by Disney to make more films. A truly happy start to our fairytale.

Shyamalan would follow the huge success of his ghostly chiller with a film that gave the first indication he was a filmmaker who would polarise public opinion like no other.

Unbreakable (2001) is the story of David Dunn (Willis again) as a man who is unsatisfied in his life, floating along in an unsuccessful marriage, and struggling to connect with a son who idolises him. Themes of acceptance are common in Shyamalan’s work, from the aforementioned Praying with Anger to Dunn’s journey of self discovery that leads him to believe he is one side of a balanced order of superheroes.

It is the uneven equilibrium in tone that distanced many viewers from making Unbreakable a huge box office hit. The majority of viewers didn’t know what to expect and those that had punctured the veil that shrouded the films production went along expecting a superhero movie and were disappointed by the slow pace of the film and its foundations in reality, when in hindsight it is probably a more accomplished set-up movie than any of the Spider-Man or X-Men springboard movies. Rumours continued after the films release that Shyamalan had planned the story arc as a trilogy, with Unbreakable being the origin movie, followed by the main plot developments in the second instalment, and the final film being the battle with Samuel L Jackson’s superhero antithesis, Mr Glass. A further example of the imagination of Shyamalan as a storyteller…….if its true! (Every story needs fantastical elements, even a Close-Up feature!)

Once again, the film hinged on a “twist” that although effective wasn’t as jaw dropping as The Sixth Sense and began to tarnish him, even this early, as a director with very little to offer but meandering plot with a last reel trick to salvage proceedings.

It had also become obvious that aswell as being inspired by Steven Spielberg, Night’s movies shared something else in common with “the beard’s” output. The Family Unit. The struggle of the single mother dealing with her son “seeing dead people”, and the true theme of Unbreakable being the restoration of the patriarchal order in the family.

His next film also featured a fractured family, some crop circles, and some poorly rendered CGI aliens who were stupid enough to invade a planet covered in water. Signs (2002), was the story of a priest, in the form of Mel Gibson, who had turned his back on his faith after the death of his wife. As if this wasn’t enough the world is just about to be invaded by walking bean sprouts.

Shyamalan is a director in the truest sense of the word. He uses very little CGI and when it is required it is for he benefit of the story (Are you listening George Lucas?). His shots are always effective in their simplicity, sometimes holding shots for an eternity while very little develops onscreen. Where his films excel, and with Signs in particular, are in the sound editing department. Most of the action takes place off-screen, a glimpse of a hand here, a leg protruding from the cornfield there, each accompanied by a jolting sound or, in another unwanted comparison to Hitchcock, the Bernard Herrmann style score.

Once again this chapter in Shyamalan’s bedtime story ends in a similar fashion. It’s make or break with the now infamous twist. A certain amount of patience needs to be given to any of Night’s films and if the more divine approach to the finale to his invasion movie isn’t accepted then it makes what’s proceeded it, no matter how effectively scary, redundant in outcome. The audience won’t leave the auditorium discussing the dark comedy or the highly emotional scene of the family tragedy, or even the alien attacks, it will all be about the twist. Sigh!

A trip to The Village (2004) also saw a fantastic, slow burning premise fall apart in the eyes of some with the tedious expectations of the twist. The problem with “An M. Night Shyamalan film” had become that everyone was trying to second guess the director and not enjoying the film they were consuming. At this stage the diminishing returns of box office receipts (The Village opened with $54M and set the record for the highest opening to lowest total gross at the US box office and was a complete turnaround from the effect of word of mouth experienced with The Sixth Sense) had been noticed by Disney who had given him unprecedented free reign over all of his movies. This was about to change.

It is here that our story moves to its unhappy ending. The fifth and final film to be made under the Disney banner was to be Lady in the Water (2006). Shyalaman’s most personal, and original film to date. Touching on all of the themes covered in his back catalogue and woven around a story first told to his young children that spanned endless nights, Lady was about a nymph from the blue world called Story who ends up in our world, and must fight the forces of evil in order to return. It was delivered without irony and without the hint of a twist but as a perfect platform for an undoubtedly creative director to paint on the cinematic canvas.

Numerous drafts had been handed in, re-written, and re-submitted by the time the sixth version was delivered to Disney as the working script. It was met with a resounding “I don’t get it”. This is a response that has been shared with critics and audiences alike as Shyamalan’s supposed self indulgence on his films has manifested in his worst box-office returns and the film being released under the Warner Bros. banner.

What effect this unforeseen twist in the career of Shyamalan has on his future output remains to be seen but he is a director with a unique vision, and one who allows the film fans (us) to discuss his movies, for good or for bad, until the curtain comes down.

“When people come out of this movie,” he says, “I hope they feel a sense of hope for themselves and for others; hope that everybody finds their purpose and we’ll be able to do what we’re supposed to do on this planet.”

This storyteller for one is glad that Night found what he was supposed to do.