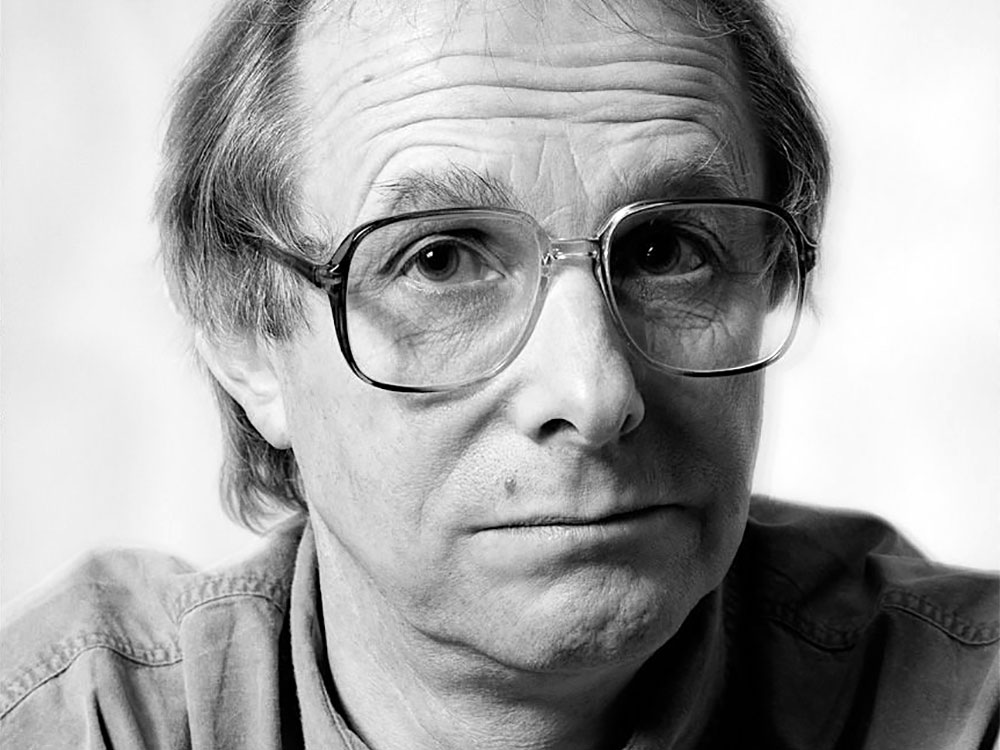

A look at one of Britain’s foremost directors renowned for his social conscience filmmaking.

Telling the truth has never really worried Ken Loach. His signature mix of fact and fiction in his film and television work has spanned five decades and never failed to live up to accusations of social realism. For Loach the telling of factual events in a film environment is a powerful tool to convey his message of social injustice writ large. For his critics he irresponsibly blurs fact and fantasy to further his own political ends. Nowadays in a ratings driven film industry Loach’s powerful tales of the disenfranchised and marginalised or his post September 11th ponderings are passed over by the mainstream filmgoer and the struggle of an exploited Mexican maid get a yawn next to Maid in Manhattan.

Loach began his career in television, changing the course of British television history at a time when not only everything was displayed in black and white but so was its conscious. In the early 1960’s the BBC was looking for TV dramas that would resonate with a mainstream public audience. Television dramas had previously concentrated on high-brow classic theatre or rather stiff, very carefully acted plays recorded live in the studio. So BBC drama boss Sydney Newman came up with The Wednesday Play to showcase new writers and establish a turning point for the TV drama. Opening in true controversial style, Newman started as he meant go on with a play written by a real-life convicted murderer.

Playwright Dennis Potter also contributed to the series early in his career. Having made his television directorial debut in Z Cars, Loach began directing several of the Wednesday Plays (winning the British Television Guild’s TV Director of the Year in 1965), and scoring some notoriety with his adaptation of the Nell Dunn novel Up the Junction (1965). It was here that he began his collaboration with producer Tony Garnett (who went on to make Earth Girls are Easy). Together they worked on a distinctive style of filming, producing more documentary influenced plays for the series, taking them outside the studio and filming on location with 16mm equipment. But Loach was to put the Wednesday Play firmly on the map with Cathy Come Home (1996), a desperate tale of homelessness that was as groundbreaking for the series as Sydney Newman had intended, leading to a change in UK law and the formation of the charity Shelter.

The road for Loach’s interpretation of real-life social struggle had already been laid by the likes of Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) about the love life of a factory worker in the East Midlands and Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey (1961) about a working class white girl who gets pregnant by a black sailor and forms a friendship with a gay man. Part of the British social realism film movement, their controversial, gritty subject matter was in sharp contrast to the 1950s sci-fi and horror fantasies that preceded them.

These directors formed a film movement in Britain called Free Cinema based on personal observation of everyday reality and in contrast to what they saw as the artificiality of Hollywood. Their work was an affectionate study of their subject with a Marxist and liberal bent. In France Jean Luc Godard had also been experimenting with politics and cinema, making films about people’s everyday lives rather than about escaping from them, particularly in his Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1967) about disenchanted Parisians.

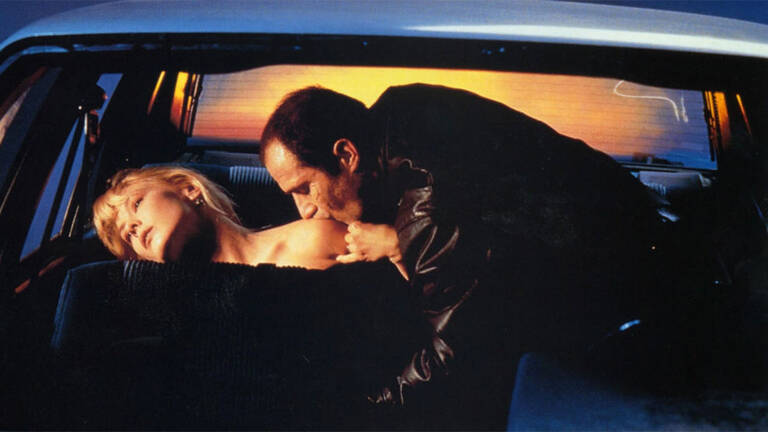

Following in a similar vein to these free-thinking directors with films such as Up the Junction (1965), Cathy Come Home (1966), Poor Cow (1967) and Kes (1969) Loach was beginning to find his niche, giving a voice to the underdog by engaging the audience through the medium of film and thus, hopefully, getting them to confront social deprivation. He used the by then popular cinema-verité technique of the hand-held camera, grainy 16mm film stock, location settings with natural lighting, accidental sounds and improvised acting, using the camera as a tool of observation rather than letting it dictate the action.

However, this very stylised and alternative approach to filmmaking occasionally worked against him by attracting a bourgeois intellectual audience and alienating those whose lives he was depicting on screen. His films therefore tended to reach a smaller, less commercial audience who were already aware of his highly politicised discourse.

After his seminal plays and films on abortion, homelessness, young motherhood and child abuse, Loach began to develop a reputation for making outspoken political studies that raised his personal profile but relegated his films to censorship obscurity. It was now the 1970s and the beginning of the Conservative Thatcher government and a low point in Loach’s career.

A rise in unemployment, the miners’ strike and drastic cuts in arts funding saw the beginning of some dark but politicised years in filmmaking. Loach reacted with militancy and his A Question of Leadership (1981) about the Thatcher government was refused airtime as was Which Side Are You On? (1984) about the miners’ strike. So began a frustrating period of inactivity as Loach found it increasingly difficult to obtain funding for new projects.

A Jury Prize at Cannes in 1990 for Hidden Agenda gave this most resilient of directors the shot in the arm he needed to return to the British film establishment, happily embracing the non-commercial and anti-mainstream. His initial outings Riff-Raff (1991), Raining Stones (1993) and Ladybird Ladybird (1994) all followed the familiar narrative of people struggling to live with poverty in an unforgiving society, and Loach is to be commended for seriously tackling issues that other directors can only approach via the romanticised-comedy route of Full Monty, Lock, Stock. and Two Smoking Barrells or Billy Elliot.

Mike Leigh is perhaps the only other successful British director who depicts similar content to Loach, but Leigh’s tragic-comedy approach with his highly acted, larger than life characters is often criticised as patronising and cruel.

Loach’s improvisational style and verité production values are incorporated into relatively mainstream films today and have become an accepted technique for more discerning audiences, providing a refreshing alternative to the slick and formulaic Hollywood fare on a sprint to the box office. Shooting his films in sequence, Loach gives the actors as little information about the story as possible feeding them a few pages of script a day to ensure that their reactions are fresh and spontaneous.

He is known for preferring non-professional actors, hiring real janitors on Bread and Roses (2000) and trawling drug projects and unemployment football teams for the supporting cast in My Name is Joe (1998). It is during this casting process Loach says he finds much of the inspiration for his films. Ricky Tomlinson said of his time making Raining Stones that there was no rehearsal for scenes and to Loach everything was a take.

Disillusioned with filming in LA and finding it easier to film in Nicaragua (Carla’s Song, 1996), this most British of directors returned to the UK to film a story of disenfranchised youth Sweet Sixteen (2002) and is currently working on Ae Fond Kiss (after a Robert Burns poem of the same name), about racism in working class Glasgow.

This socially responsible content about real lives has brought Loach back full circle to producing films that feel like extended editions of the BBC’s Play for Today (what the Wednesday Play became when its highly politicised content began to turn viewers off), along the lines of Stephen Frears’ My Beautiful Launderette or Jim Sheridan’s The Boxer.

As his filmmaking spreads to further shores, Loach is hopefully reaching new if not wider audiences. It is somehow comforting to find that just as the northern accents and language in Kes was deemed incomprehensible and so subtitled for audiences in 1969 so some 30 years later Loach’s realistic Glaswegian dialogue was subtitled for the American audiences of My Name is Joe.

Alan Parker said Ken Loach “reminds you always that you shouldn’t become a filmmaker unless you have something to say”, and the Oxford graduate from Nuneaton has never shied away from vocalising what’s on his mind and reflecting the mood of a nation or people. Having moved through the social welfare inadequacies of the 1960s, railed against the Thatcherite policies of the 1970s and 80s, coming back round to focus on issues of poverty, addiction and racism in the 1990s, it will be interesting to see how the new century inspires this celluloid Robin Hood.

Rebecca Kemp

Ken Loach’s film biography:

Poor Cow (1967)

Kes (1969)

The Save the Children Fund Film (1971)

Family Life (1971)

Black Jack (1979)

Looks and Smiles (1981)

Fatherland (1986)

Hidden Agenda (1990)

Singing the Blues in Red (1990)

Riff Raff (1991)

Raining Stones (1993)

Ladybird, Ladybird (1994)

Land and Freedom (1995)

A Contemporary Case For Common Ownership (1995)

Carla’s Song (1996)

The Flickering Flame (1997)

My Name is Joe (1998)

Bread and Roses (2000)

The Navigators (2001)

Sweet Sixteen (2002)

11’09″01 – September 11 (Director of UK segment, 2002)

Ae Fond Kiss (2004)