Liz Hyder looks back at the German director who was courted by the Nazis and obsessed with making films about a serial killer.

With a life as dramatic as his films and a career parallel to Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang remains one of the most enigmatic and inspired storytellers in the history of cinema. The creator of films as diverse as Metropolis, The Big Heat and the deeply disturbing M, Lang also dabbled in musicals and westerns with You And Me and Rancho Notorious and made a whole series of films starring the sinister criminal Dr Mabuse.

An enemy of the Nazi movement and everything they stood for, Lang’s films often have a strong moral thread running through them. Like his more famous contemporaries, Hitchcock and Renoir, Lang is often cited as one of the few true auteurs in cinema and his strong social and artistic concerns can be traced right through his diverse portfolio of work.

Born in Vienna as the son of an architect, Lang fell into the family line of work and trained first as an architect himself before upping sticks and moving to the social whirl of 1920s Paris to set himself up as an artist. Called back to Vienna as war broke out, Lang was conscripted into the Austrian Army and fought in WWI in which he was badly wounded.

It was whilst recovering in hospital, that he began writing screenplays and, after the war had died down, Lang moved to Germany’s UFA studios first as a script-reader and then as a director. The Expressionist movement was already on the wane when Lang moved to Germany, but it clearly left a strong impression on him. In 1922, following Lang’s first taste of success with Between Two Worlds (the inspiration behind Fairbanks’s The Thief of Baghdad), Lang made the first of his Dr Mabuse series, the portrait of a master criminal.

Mabuse is a fascinating character as, like the later M (1931), Lang shifts the sympathies between the criminal and what would otherwise be seen as the force for good (in Mabuse this is represented by the police, in M it is the public). Lang is equally critical of the social systems that create a destructive monster, like Mabuse or M, as the monster themselves.

Interestingly, Mabuse can also be read as an early example of what would later become a recurring theme, that of not trusting appearances. Mabuse is a power-crazed criminal who attempts to control events and other people through use of disguise and cunning, and in M, Peter Lorre’s child murderer is a wide-eyed respectable man who looks perfectly normal and yet is an obsessive destroyer of childhood.

Mabuse was also an influential character in that he changed the direction of Lang’s career and prompted a move from Germany to the heady heights of Hollywood. After his follow-up film, The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1932), Lang was asked by head of Nazi propaganda, Josef Goebbels, a fan of the film, to supervise Nazi film production. Lang turned the offer down and fled for Paris leaving his wife, Thea von Harbou behind along with most of his belongings.

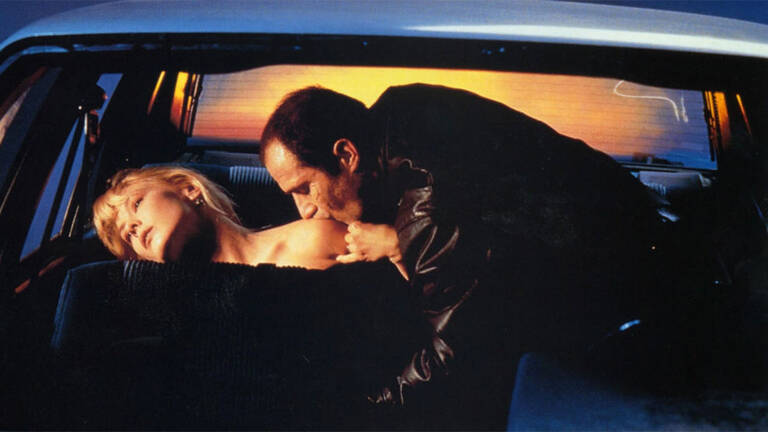

Thea later divorced him and became a fully paid up advocate of the Nazi party much to Lang’s disappointment but his own life had already moved on in a very different direction. He moved to Hollywood in 1934 (on the basis of a one picture deal with MGM) and, for the next two decades, made a wide variety of films across several genres. The best known perhaps is still 1953s The Big Heat, a police thriller in which Bannion, a policeman, becomes obsessed with seeking revenge for his wife’s death and finds himself embroiled in the criminal underworld himself.

A heady and powerful drama, there are strong echoes of Expressionism in the style of this cool film noir. Lang’s career in the States ended on a somewhat sour note after tensions with producers reached breaking point. Lang packed his bags and after a brief sojourn in India, returned to Germany where, in 1960, he directed his last film The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse, his final tribute to the criminal character he was so excited by.

Lang is difficult to pigeon-hole as a director and, like his contemporaries Renoir and Hitchcock, it is precisely because of this that he is so endlessly fascinating. His work too can be split into two very different periods and styles, his German era was stylised to the point of being closer to theatre than film whereas his American era is more subtle and closer to the naturalistic style so prevalent in today’s cinema.

Some of his films are now so iconic, it is difficult to imagine cinema without them – from the insect-like workers and futuristic skyline in Metropolis to Lorre’s hounded child murderer in M, from Gloria Graham’s burnt face in The Big Heat to Marlene Dietrich’s cool card-playing in Rancho Notorious – Lang was a truly revolutionary and innovative director.

In recent years, evidence has come to light that suggests Lang had tendencies towards stretching the truth of his own life story, but this unexpected Baron Munchausen element merely serves to strengthen the myth of the man and his remarkable portfolio of films. Lang himself would probably be delighted by this new angle on his life as, after all, it was debate that he wanted to provoke through his film-making.